On a soft October evening in London, Basil Moftah stood at the top of the staircase inside the Design Museum, looking out over a room filled with Gulf founders, London venture capitalists, sovereign fund representatives and a scattering of European and US dealmakers.

"Middle East and Saudi technology companies are rising," he began. "Behind the headlines and photo ops, They are scaling fast, solving problems that impact people day by day. There's a tipping point coming, one that will take this ecosystem to another place. Keep building. Keep doing what you're doing. It is the reason why we exist."

The room quieted as he shifted to the personal. "For years, I believed the region had the same depth of talent as any market I’d worked in. From San Francisco to London. What we’re seeing now is that talent meets capital, structure, and belief. It’s no longer potential; performance, the region is ready for the global stage."

That evening's Saudi Ecosystem Investor Mixer was the visible surface of something assembled months earlier, a careful choreography designed to convert foreign investor mandates into actual capital deployment.

The architecture behind the event

Where most regional conferences favour scale and spectacle, the Key Capital London Trek, now in its third year, is built on the inverse: scarcity and precision. Backed by partners including Jefferies, Taylor Wessing, QED Investors, 500 Global, Hub71 and Saudi Arabia's Ministry of Communications and IT, only a few dozen founders are selected and nearly every investor meeting is deliberately arranged. "It's something curated," Moftah explained later, "a personalised agenda that cuts through a lot of the bullshit."

What gives the Trek its weight isn't what happens in October but arguably what happens in March, April, and July, when Moftah and Abdo Edris quietly crisscross London, meeting growth and crossover funds, mapping appetite sector by sector, and deciding which companies can credibly carry the ecosystem's story. This months-long preparation determines everything: which sectors make the cut, which founders get selected, which investor-founder pairings have genuine potential.

"There's arguably more capital available in the UK for Middle East startups than there is in the Middle East," Moftah says. The investors are already structurally capable of deploying into the region; they simply haven't. The Trek's purpose is to turn that latent capacity into capital, to make the region not merely legible but impossible to ignore.

For years, that capital lay waiting in the wings. But clearer routes to liquidity through regional exchanges have begun to catalyse deployment, moving exit pathways for tech companies beyond the realm of theory. Talabat debuted on the Dubai Financial Market in December 2024 at a valuation of roughly $10.1 billion. Rasan had already listed on Tadawul earlier in the year, while Dubizzle, backed by Prosus, has just launched its investor roadshow ahead of an expected DFM listing before the end of 2025. Investors now see a market capable of absorbing scale.

Regional momentum

The data bears out the shift. According to MAGNiTT, venture funding across MENA reached $3 billion in the first nine months of 2025, the strongest performance on record and, for the first time, ahead of Southeast Asia. This wasn't sudden growth; it was acceleration across a narrowing band of the capital stack.

For the most part, this expansion has concentrated in larger Series A and B rounds – fewer deals, but deeper commitments. Much of that weight has settled in the UAE and Saudi Arabia, where deployment has accelerated sharply. Fintech remains the most capitalised sector, and M&A activity has already overtaken last year's totals. Foreign investors now account for a steadily rising share of that capital.

The expansion in funding has been accompanied by something less easily measured: a recalibration of global attention toward the Gulf. Earlier this year, Donald Trump arrived in Riyadh with a delegation of major Silicon Valley investors, a gesture that signalled Gulf tech had moved from diplomatic afterthought to investable infrastructure.

More concretely, in September, Saudi Arabia approved landmark reforms allowing majority foreign ownership of companies listed on Tadawul. The change added $124 billion in market cap in a single day, widening liquidity channels and opening clearer exit pathways for founders. For international investors, this meant real optionality: you could now build companies in the region and have concrete paths to liquidity.

It is against this backdrop that the Trek, held from 29 September to 3 October, assumes its weight. Its aim is not to introduce the region to investors, but to convert mandate into action. The funds in the room already have the legal structures, LP allocations and cross-border capacity. What they have often lacked is a compelling reason to deploy.

"The majority of these investors are active in the region," Moftah said. "But there's a large amount that have mandates that cover the region, but for one reason or another haven't done any transactions. They've agreed with their LPs that they will have an international allocation, but nobody ever gets around to their opportunistic bucket."

The deliberate curation

This year's Trek brought together 35 founders, from Seed to Series D, for more than 280 one-on-one meetings with 45 global investors. The decision to keep the programme small is entirely deliberate.

"The big differentiator is quality over quantity," Edris said. "The investor has read the profile and made a conscious decision to meet the founder. Ninety percent of the meetings are investor-initiated."

That filtering begins months before anyone boards a plane. In July, Edris and Moftah sat with funds to gauge appetite sector by sector. There was little interest in EdTech; fintech, SaaS and AI dominated the shortlist. The shape of the Trek is determined long before it starts.

Within this context, every founder selected for the Trek carries more than a company. The selection process privileges articulation, credibility, and the ability to hold the weight of representation. "We're not just taking any random founder that wants a big check," Edris said. "You have to be a good company and a good founder – someone who can represent the region well."

The pressure of representation

Each meeting is therefore a reputational node in a wider network: one strong encounter can open doors for others; a weak one can quietly close them.

The old perception of the MENA startup scene as marginal has fallen away for global investors, not through rhetoric, but through lived experience. In London, conversations between founders and some of the world's largest funds no longer began with an explanation of the region; they began with comparisons.

"We honestly thought we'd spend half the time explaining what the Middle East is and how things work here," one founder said. "But once we started talking to the big VCs it flipped. We'd barely started explaining what we're building and they were already drawing parallels to what happened in Europe five years ago."

Another founder described the Trek as "one of the most thoughtfully put-together global programs we've ever joined." What struck them wasn't the number of conversations but their depth.

The capital stack problem

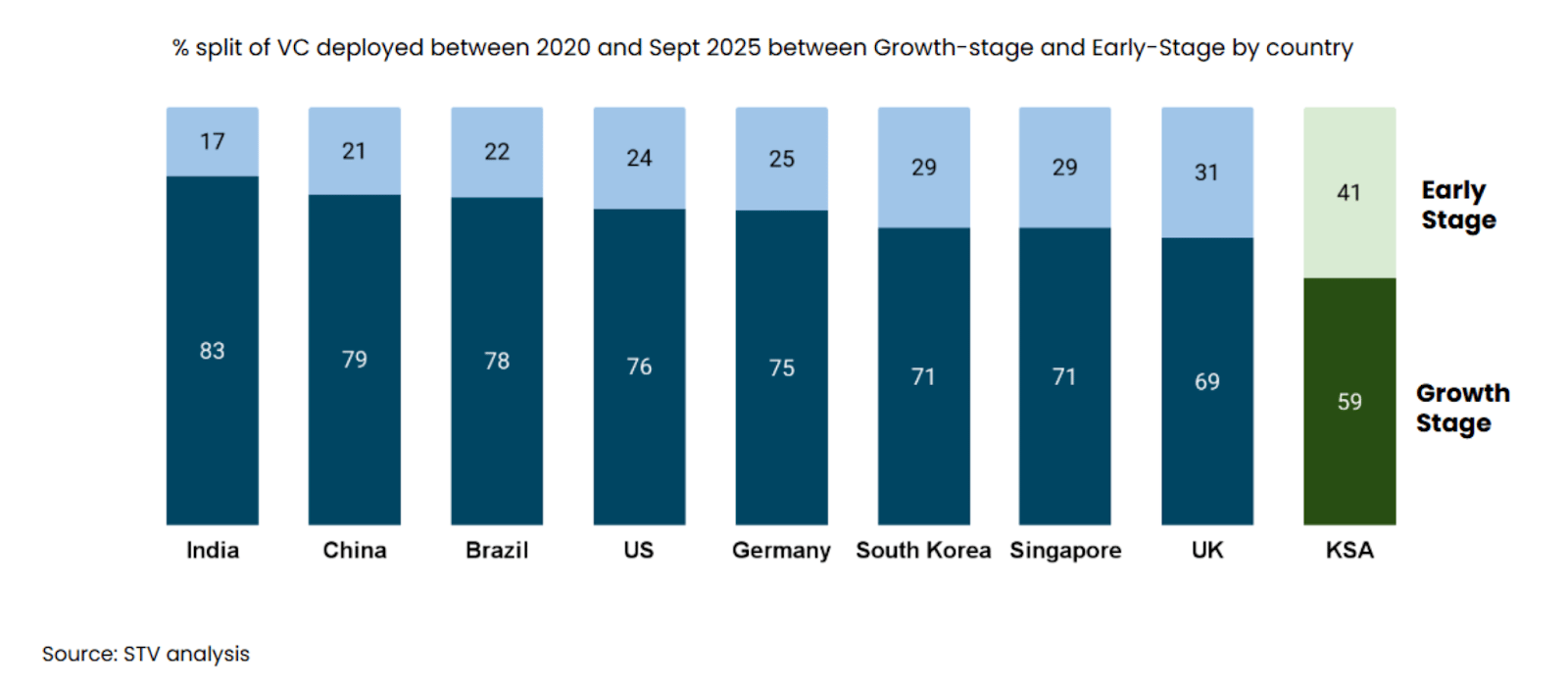

Those interactions point to an underlying tension in the region's venture market: early-stage capital is plentiful, but growth-stage funding remains thin, despite the launch of a number of new growth oriented regional funds over the past 12 months from 500 Global to BECO Capital. According to STV, the gap between the two still stands at roughly $16 billion.

Bridging that gap depends less on a single breakthrough than on building the plumbing beneath the market. One part of that architecture is liquidity. Secondaries, transactions in which investors purchase existing shares rather than issuing new ones, are becoming a practical bridge between ambition and capital.

Moftah noted that inbound interest in secondaries has grown sharply as Key Capital moves toward the first close of what remains the region's only dedicated fund of its kind. The shift is mirrored globally: only last week, Goldman Sachs announced its $965 million acquisition of Industry Ventures, a signal of how secondary markets have moved from the margins to the centre of capital strategy.

The same logic is also taking root locally. Wamid, the technology arm of Saudi Tadawul Group, has partnered with STV to build a digital trading platform for private-company shares, a secondary market aimed squarely at Saudi startups and SMEs. For MENA founders, this means exit pathways are no longer hypothetical things that happen elsewhere. Slowly but surely, these moves suggest an ecosystem beginning to develop the liquidity infrastructure required to sustain scale.

In conversations across the Gulf, IPOs have become a kind of shorthand. Founders and investors joke that by 2027, the Tadawul bell will bear the mark of repeated use, a light way of acknowledging that credible exit pathways are no longer a thought experiment. But the real story lies in the scaffolding that precedes any listing: venture debt, structured products, and now secondaries, which are steadily thickening the capital stack.

The weight of reputation

The technical infrastructure, though, is only part of the equation. The rest is human choreography: the expectations embedded in every introduction, the weight of collective reputation.

"This whole thing is predicated on leaving a good impression," Moftah said. "If we've leveraged our goodwill to make introductions, we expect the founders to do proper follow-up. We don't want to leave a bad impression for the region."

In a market where perception still travels faster than capital, reputation compounds. Every founder on the Trek carries the credibility of the ecosystem itself. When those interactions land well, foreign mandates move from paper to deployment. When they don't, the opportunistic bucket stays closed.

That is why the Trek has deliberately remained small. More meetings might generate noise; fewer, better ones shape how capital behaves. It is also why the team agonises over investor–founder matching months in advance and quietly cuts entire sectors when appetite is low. Unlike a conference, there is no panel to hide behind. Every meeting matters.

This article is part of FWDstart’s partner programme series. We follow stringent editorial standards, and while we collaborate closely with our partners, final editorial control rests solely with FWDstart to ensure the authenticity and creativity of our content. All partnerships are disclosed clearly, and we only collaborate with organisations we genuinely admire – Key Capital is one of them.