When Adam Cheyer began working with computers in the early ’90s, he believed, as science fiction had for decades, that the most natural way to interact with machines would be through conversation.

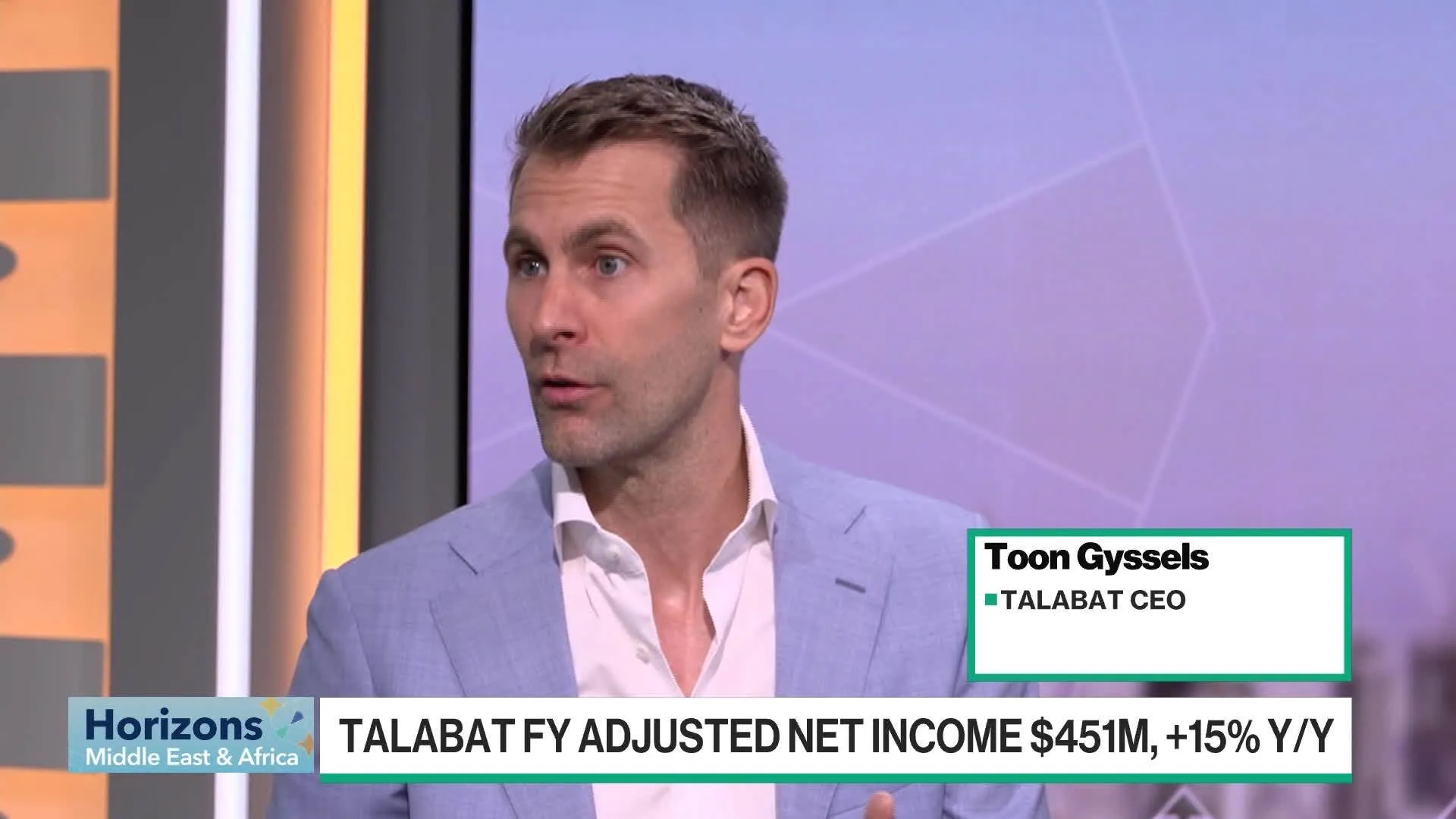

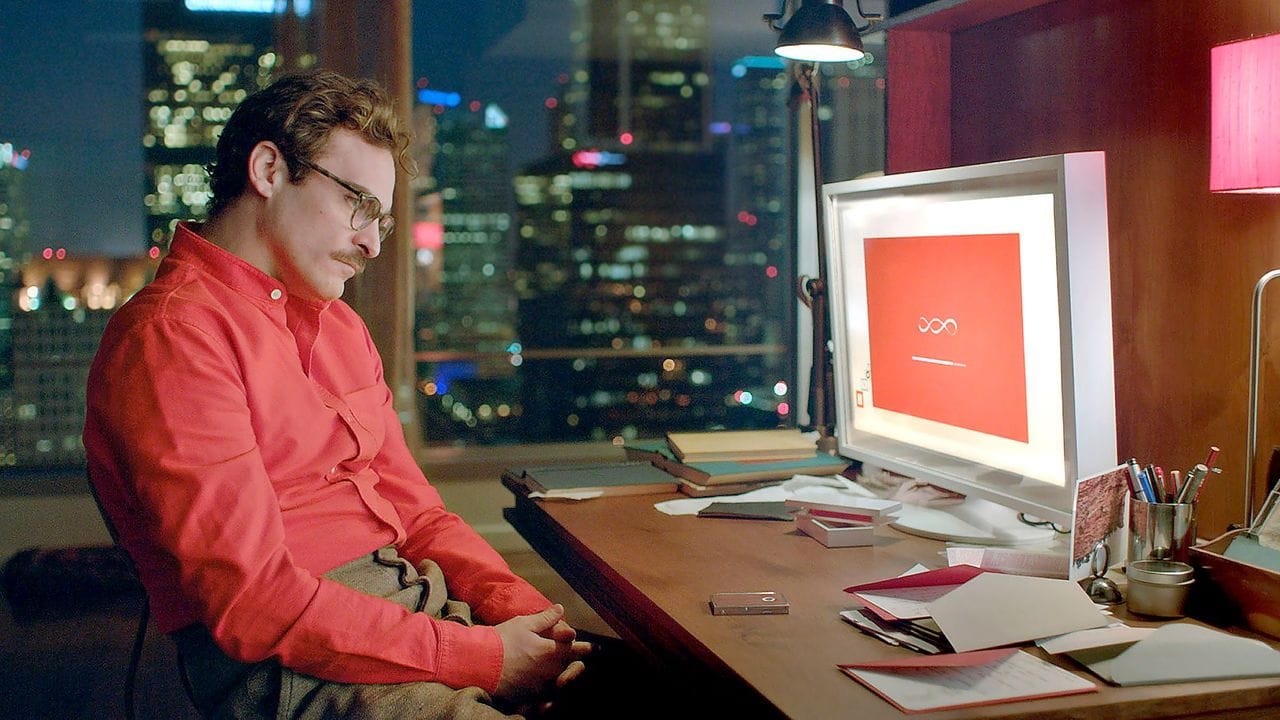

From HAL in 2001: A Space Odyssey to Spike Jonze’s Her, voice has long been the medium through which AI elicits our strongest emotions, from fear to intimacy.

“I am putting myself to the fullest possible use, which is all I think that any conscious entity can ever hope to do.”

In 1993, Cheyer built an early prototype of a learning, adaptive digital assistant. Two decades and 50 iterations later, he and his colleagues launched the fruits of their labour, Siri, as an iPhone app in 2010. Two weeks later, Steve Jobs called. Apple bought Siri for $200 million, and then left it largely fossilised in amber.

What’s striking is how little the vision has changed. Watch Siri’s 2010 demo next to ChatGPT’s voice mode and the core use cases are almost identical: asking questions, retrieving information, scheduling, getting recommendations.

You see, for years the gap wasn’t imagination, it was compute. Early assistants were narrow in scope, robotic in tone, and trapped in the uncanny valley. That constraint, thanks to Jensen and GPUs, has now lifted.

Large language models are capable of sustaining context-rich dialogue; speech systems sound convincingly human; latency has dropped from seconds to milliseconds; interruptibility and imperfections, hallmarks of human communication, are now seamlessly woven in.

This progress is happening at breakneck speed. Improvements in model design and infrastructure have cut response times and boosted performance, much of it in just the past six months. Costs are collapsing too: OpenAI’s December 2024 pricing reset cut GPT-4o Realtime API costs by 60% for input and nearly 88% for output.

It’s this combination of capability and cost that led a16z, in its latest AI Voice Agent update, to declare that conversational quality (latency, interruptibility, emotion) is now “largely a solved problem,” with voice agents equalling or outperforming BPOs and call centres.

But is that true across geographies, most especially MENA, or is Andreessen’s view filtered through the red-white-and-blue lens of American Dynamism?

“This is a land-grab moment,” Fouad Jeryes, co-founder of Riyadh-based Maqsam, a cloud communications platform building Arabic-first AI voice capabilities for the region, told me. “The opportunity across these fragmented regional markets is real. It’s time to bring them together.”

If recent YC cohorts are any indicator, he may be right. Voice companies made up 22% of the last batch, according to Cartesia, a signal that MENA could be on the cusp of its own breakout scramble.

That is, if it isn’t already underway – funding rounds for two regional AI voice agent players, Sawt and Wittify, in just the past month suggest competition is already heating up.

So with all of this this in mind, let’s map the terrain and examine why voice is arguably the most resonant emerging AI communication medium; how Arabic dialectical diversity complicates matters; the regional use cases and verticals; the competitive landscape; and what might be coming next around the corner.

Many thanks to Fouad Jeryes, Co-founder & CBO at Maqsam, and Bashir Alsaifi, Co‑founder & CEO of DataQueue, for their time, insights, and valuable contributions to this piece.

Why voice?

“Voice is one of the most powerful unlocks for AI application companies. It is the most frequent, and information-dense, form of communication, made programmable for the first time due to AI,” notes Olivia Moore, a partner on the consumer investing team at Andreessen Horowitz.

To appreciate why, let’s embark on a very brief science lesson.

For starters, speech predates writing by ~150,000 years, meaning our auditory systems are hard-wired to process voice far more naturally than text.

Research from University College London and Princeton (Banse & Scherer, 1996; Cowen et al., 2019) shows that prosody – rhythm, pitch, intonation – can reliably convey more than 20 distinct emotional states without the listener ever seeing the speaker.

The superior temporal sulcus in the brain (if your anatomy’s rusty, it’s the bit tuned to voice) is specialised for decoding these signals, making spoken words feel richer and more “alive” than flat text.

Human voices even trigger oxytocin release (Zak et al., 2005), deepening trust and social bonding. Micro-signals such as breath, pauses, and tremors act as authenticity markers we instinctively detect.

Superior temporal sulcus

For enterprises, cultivating trust has clear monetary value.

Voice agents can run thousands of conversations simultaneously, operate 24/7, and deliver consistency that outperforms humans on both cost and customer satisfaction. Time zones no longer matter. Engagement, retention, and conversion rates all rise when voice is the interface.

For consumers, it may become the first, and perhaps primary, way they interact with AI: a coach, concierge, companion, or, more unsettlingly, lover. Spike Jonze’s Her looks more prescient with each passing year.

The linguistic challenge

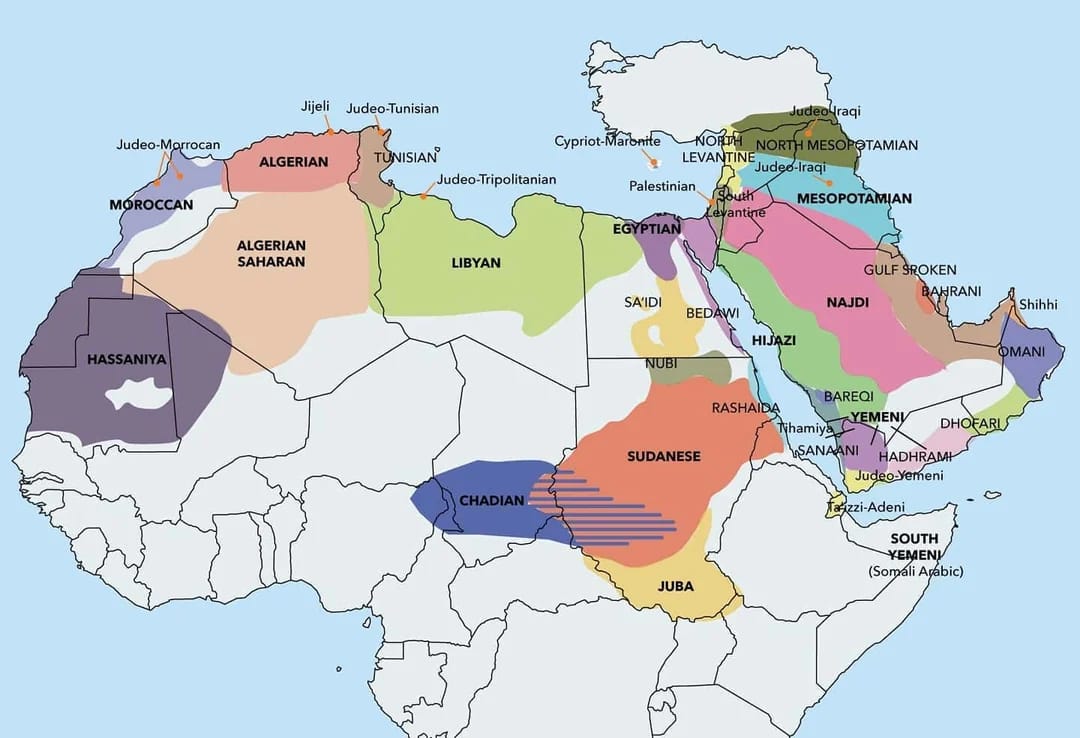

As we outlined in a deep-dive last year, progress in Arabic AI voice has long been stymied by the language’s structural complexity: at least 25 dialects, a formal written register coexisting with diverse vernaculars, and a script dense with diacritical markings and inflected letters.

Add in frequent code-switching with English, and in places like Lebanon or North Africa, French, and matters get even messier.

“We often mix Arabic and English,” said Maqsam co-founder Fouad Jeryes. “Spoken Arabic really becomes a completely different language, with major differences even between dialects. Some words in Emirati can mean something totally different in Jordanian Arabic, sometimes even a swear word. You get a lot of false positives, and you really need to catch that nuance.”

Map of Arabic dialects

Across the…

The remainder of this article is for paid subscribers

This is premium content. Subscribe for just US $0.27 per day to read the full story.